Nearly four years ago, Justin Mach, an engineering specialist at Caterpillar, was invited by Armand Beaudoin, associate director of Insitμ, to work with CHESS on materials research that could be of benefit to the company. Mach conducted Caterpillar’s first experiment with CHESS in December 2014 to help validate a model of how residual stress occurs during welding. Caterpillar has continued this collaboration with both CHESS and the Advanced Photon Source (APS) to aid in further research and development in welding and in other processing stages of materials.

The collaboration between CHESS and Caterpillar Inc. shows that advanced scientific research centers are not just for scholarly research, but can also be tools in industrial development.

Justin had never performed research at a synchrotron before coming to CHESS. His unique perspective can give insight to both industrial users and to students preparing for a career in engineering. We sat down with Justin to ask him a few questions about his experiences at CHESS.

How did you get involved with CHESS?

My graduate school advisor, Armand Beaudoin, reached out to me in the Fall of 2014 with an interesting proposal to collaborate with the newly formed Insitu@CHESS center on materials problems of interest to Caterpillar. It was particularly good timing, as we were working on a research project that required extensive validation of welding residual stress predictions. The collaboration moved quickly, and our first experiment at CHESS in December 2014 focused on residual stress measurements in a small welding sample designed for the equipment available at CHESS at the time. Since that time, we’ve performed several experiments with Insitu@CHESS staff at both CHESS and the Advanced Photon Source (APS) to support Caterpillar R&D in welding, heat treatment, and other process and product support.

Was there anything new that surprised you about doing research here? Or was it as you expected?

I didn’t know enough at the time to know what to expect. It was my first time at a synchrotron, and I was excited to be using such advanced technology to support our investigations. I was impressed with how collaborative and supportive the students, staff, and professors are with each other and the users.

Why is Caterpillar investing its time/money to have you evaluate your samples at CHESS? What does this say about the company's overall strategy?

CHESS has experimental and modeling capabilities that can be found only in a few places in the world.

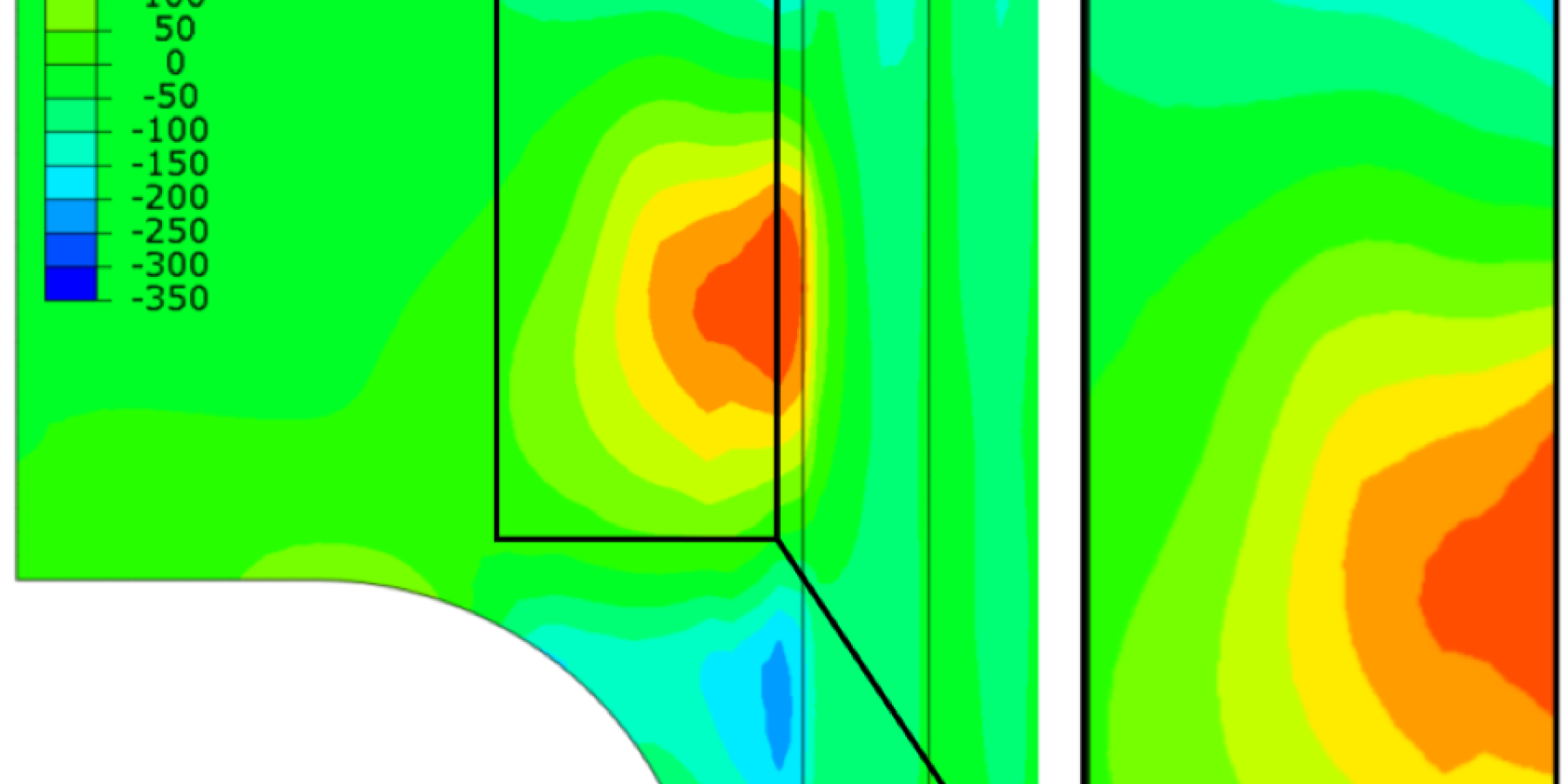

CHESS has experimental and modeling capabilities that can be found only in a few places in the world. Plus, Insitu@CHESS staff have developed the energy dispersive diffraction technique to effectively and efficiently measure residual stresses at fine resolution in large, heavy parts like the ones Caterpillar handles every day.

Has it been useful to do research at CHESS? Has it led to new ideas on how to research your materials/processes?

The results from CHESS have led to greater confidence in our welding simulation model predictions, as well as another manufacturing process. The work we did with heat-treat samples revealed a unique way of characterizing the residual stress field in the high-gradient region of surface-hardened components. Chris Budrow, a doctoral candidate at CHESS, is working toward publishing the heat-treat work soon.

What was the learning curve like to use the facility? What is it like to work with CHESS staff scientists?

CHESS is a wonderful environment for learning and education. One of the primary purposes of the Insitu@CHESS center is to bring in industry people and turn them into users of the facility. They’re doing a great job with that. I now know so much more about what’s possible at CHESS for engineering materials, which means I can help to formulate new research and educate my colleagues at Caterpillar about the possibilities. All the CHESS staff I’ve worked with have been helpful and engaged. Each synchrotron experiment is unique and challenging by nature, and the CHESS staff have always done everything they can to make sure we leave with results.

What skills can students (Undergraduate and Graduate) focus on to perform research like this, and strengthen the R&D programs for companies in the private sector? How can CHESS (and other US research facilities) enable students to achieve this?

I think it’s important that students have a good foundation in the mechanics of materials at the continuum scale and an understanding of materials at length-scales where deformation and failure initiate, such as the grain-scale in metals and other crystalline materials. Computer programming for engineering and science applications is another invaluable skill for this type of research (e.g., Python has become an extremely useful and universal scripting language in engineering and the sciences). Certainly, a background in x-ray science is useful for performing research at CHESS, but it is not a necessity and shouldnt be viewed as a barrier for industry users specifically. That’s what the CHESS staff are there for! Industry should leverage their expertise—and the expertise at similar programs and centers—to do the research that solves the problems of tomorrow.

Why do you think facilities like CHESS are important for industry? And for the future of the US economy?

Facilities like CHESS are training students to be future leaders in engineering and the sciences. These facilities bring state-of-the-art experimental and modeling capabilities to industry users to solve their most challenging problems. Industry users couldn’t afford to invest in these capabilities individually. So, having these advanced scientific capabilities and highly trained individuals propels industry forward, advances technology, and makes the U.S. more competitive globally, with a more highly-skilled workforce.