Chris Conolly looks at the concrete floor of Wilson Lab, eyeing up the numerous holes drilled by one of the contractors for the upgrade project. These one-inch holes pockmark the 10,000sf experimental hall of the Wilson Synchrotron Laboratory. In a way, these holes represent the numerous experiments conducted over the past 50 years.

It’s almost like being an archaeologist

There are a lot of holes. 652 to be exact, as the CHESS X-ray Technical Director and CHESS-U beamline project manager easily points out.

“It’s almost like being an archaeologist”, says Conolly, as he walks through the maze of newly constructed hutches in the experimental hall. He stops near the sector II hutches, “especially this spot here,” he says, presenting a repeating pattern of drilled holes arcing across the floor. The pattern spans a total of about 25 feet, and Chris, who has been with CHESS for the past 18 years, has no idea what was held down by the bolts marked in the floor.

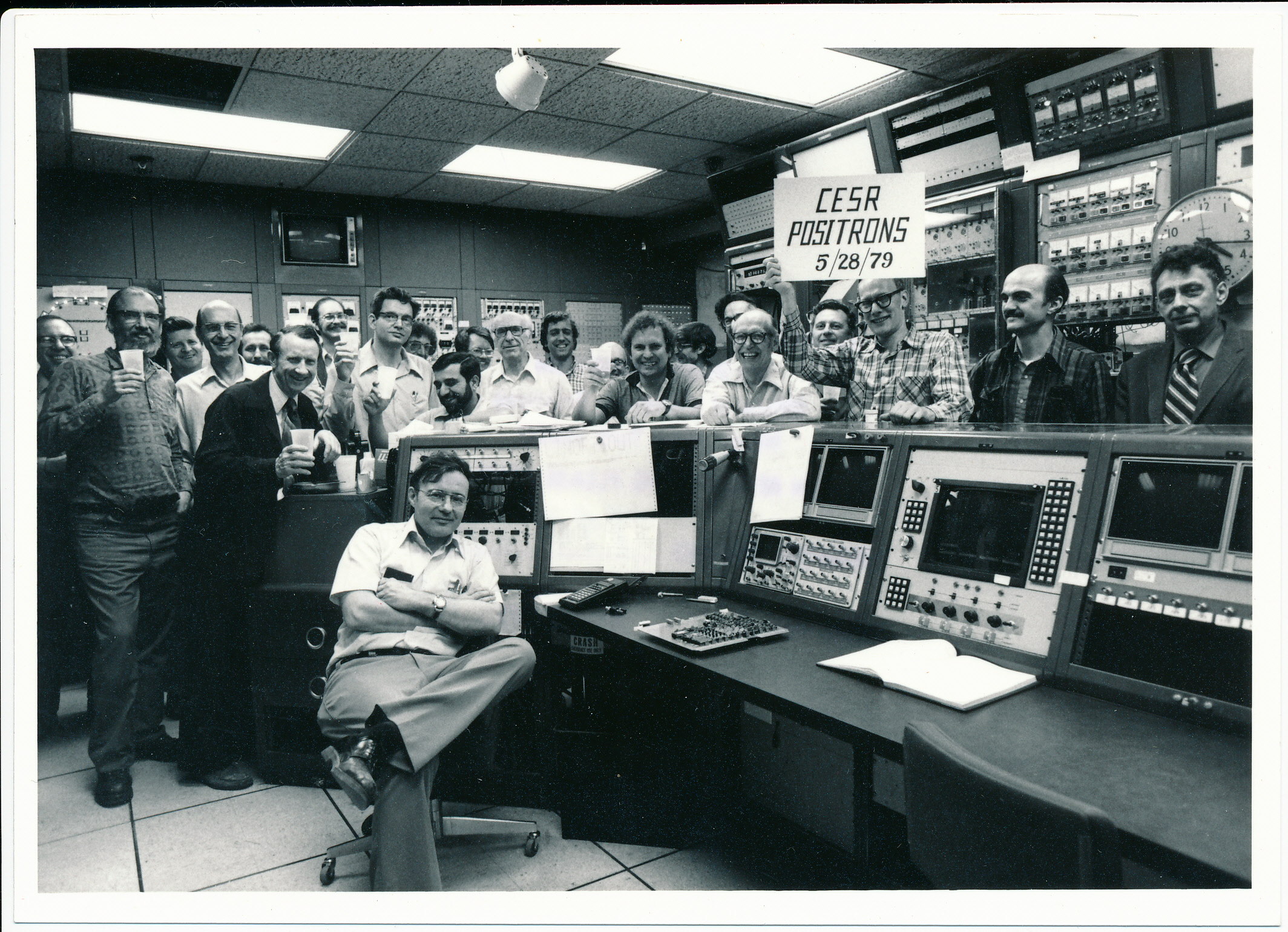

Up until four months ago, this specific area housed the West RF power for the Cornell Electron Storage Ring, CESR. But before that, he isn’t so sure. “It may have been something from the early days of the lab, before CESR or CHESS were even built. I am sure someone around here knows.”

There have been a few experiments bolted to the floor in Wilson Lab, to say the least. They span the fixed-target experiment days, from a time before scientists could collide particles together, to the DC gun for the energy recovery linac, CBETA, currently being built in the experimental hall 100 feet away.

One such experiment, the CLEO detector, was built in 1978. This was the same time as CESR, the storage ring which feeds beam to CHESS. Before this time, the lab was using only the synchrotron for research. With some foresight for future projects, CESR was designed with the space and flexibility in mind to conduct numerous and diverse experiments. However, from the time CLEO was built, until 2008, the collision of particles was the crux of Wilson Lab.

In its heyday, the CLEO project at Cornell was the longest high-energy physics collaboration in the world, setting multiple records for luminosity, and publishing more data on B-mesons and charm quarks than any other lab in the world. CLEO was later decommissioned, and removed in the summer of 2016, making space for the CHESS-U upgrade. But the holes in the floor remained, as did those of other countless projects built inside the lab.

These projects were always built around something, both scientifically, and physically. The flexibility of CESR allowed for accelerator-based research that simply could not have been done elsewhere. But physically, these experiments had to be assembled within the limitations and “ingenuity” of these previous projects.

“We always suffered with decades of cobbling together wires and piping for experiments through the years,” explains Ernie Fontes, Sr. Director of CLASSE, and who also started with CHESS in 1991. “We would always say that CHESS was a ‘wonderful onsite improvisation’, we never stopped to take anything out, clean the floor and start over. We would just work around anything that was there.

That is why CHESS-U is different. The storage ring, experimental hall, and the lab overall is fine-tuning every component to produce high-energy, high-flux x-rays. Wilson Lab has not seen an upgrade like this in decades. “When people return to the lab, I think they are going to be shocked” Fontes says. “It is almost like a ‘green field site’”, he states, referring to the projects typically not limited by prior work.

Even those little holes in the floor, created and left behind for decades, are being carefully filled with cement and buffed over, erasing any visible signs of these early experiments.

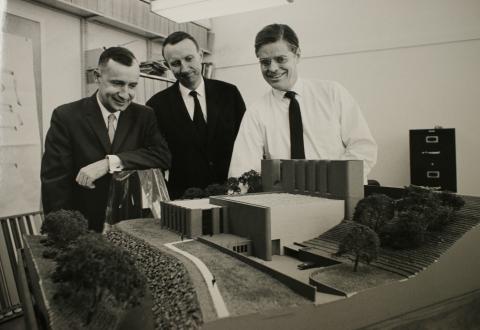

As for the unexplained pattern of holes arcing across the floor, it was indeed a fixed target experiment from the initial years of the lab. “The circle was the steel pad for a spectrometer studying photoproduction from a fixed target,” explains Don Hartill, emeritus professor of physics at Cornell, from his 3rdfloor office at Wilson Lab.

He should know. As a new assistant professor at Cornell at that time, he observed his colleagues taking data with the spectrometer while he was involved in a wide angle bremsstahlung experiment using an internal target in the synchrotron.