Q: Could you tell me a little bit about your initial experience as a community college student in the SERCCS program at CLASSE?

A: Sure, it was a fortuitous kind of situation. I remember I was at TC3 and it was my last week; I had just finished up my finals. I had already been accepted as a transfer student into Cornell for the coming fall semester. My academic advisor at TC3 had forwarded an email from Lora Hine saying that they had a last-minute drop out of the SERCCS program and they only had a few days to fill the spot for the summer; do they know any students who might be interested? I had a bit of a fascination with the synchrotron already: I had toured with Ken Finkelstein earlier that spring. My mom met him through this volunteer program that they were both involved with, and when he said he was a scientist at the synchrotron, my mom was like, “Oh my goodness, my daughter loves science and is transferring to Cornell, can you give her a tour?”

So, when I met Ken there [Wilson Laboratory] and took a tour of the synchrotron, I became enamored by it scientifically. When I saw this opportunity to work there for the summer, I jumped on it. It was perfect because they needed someone to fill the spot at Richard's beamline, which is a biological sample characterization beamline, and I had been studying biotechnology with my degree major at TC3, and was transferring into the molecular and cellular biology program in CALS at Cornell. So, it was a perfect fit. I like to think of it as just a fortuitous kind of alignment where they needed a spot filled and I was able to do that.

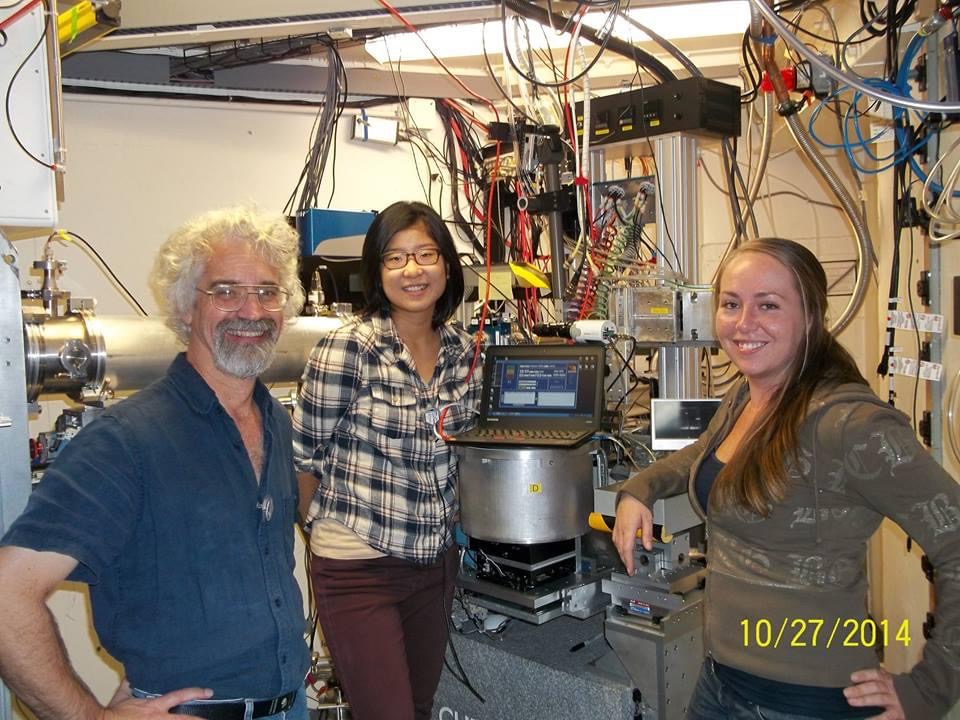

That summer I worked with Richard and also with Alvin Acerbo, who was postdoc at the time, and I did a project on the microfabrication of mixer cells. The BioSAXS beamline was using layered polymethyl-methacrylate cells that were fabricated at CNF (Cornell Nanoscale Science and Fabrication Facility). I started with the existing design and adapted it so that two samples could be mixed before being exposed to X-rays.

And that was it, I mean, I fell in love with synchrotron science, right within those first few weeks! I loved being able to have a goal and be able to engineer and figure out my way through, troubleshoot, problem solve, and to get to that end point where I could perform an experiment on my own.

Q: What inspired you to pursue undergraduate research at CHESS and what were some highlights from your projects?

A: Richard Gillilan knew I was transferring into Cornell as a student in the fall, so he connected me with Prof. Sol Gruner in the physics department and Jeney Wierman, who was a graduate student at the time. She became my graduate student mentor and that fall I started working in Sol's lab. I continued through the rest of my time as a student at Cornell working on beamline engineering projects. I started working on fabricating multilayer graphene that could be used as an ultrathin X-ray transparent window material, which we eventually did get to work at the 11th hour. It was 6:30 in the morning before the Tuesday down and Richard and I got it to work, and I wrote an undergraduate honors thesis on that project. There had been times throughout my experience as an undergrad where I was able to run my own experiment and adapt the beamline as needed for the experiment that I needed to run.

There are just not many labs where an undergraduate has that kind of experience or even has the potential for that kind of experience. I think CHESS is exceptional for that reason because they are so closely intertwined with the university that they're able to provide these educational experiences for students that they wouldn't be able to get otherwise. At CHESS, you can propose an experiment and say, “Hey, this is what I want to do, can we completely change and adapt the beamline to do this?” And they're like, yeah let's try it out (if the safety committee approves of it).

Q: How did you progress your academic career at Cornell and what made your graduate school experience unique?

A: Through being involved with the BioSAXS beamline and mentored by Richard and Sol, I was introduced to Prof. Nozomi Ando. At the time she was starting her professorship at Princeton. So, when it came time to graduate I applied to her lab and much to my astonishment (as someone who hadn’t graduated high school and entered academia through community college, this was beyond my wildest dreams to say the least), I was accepted. I moved down to Princeton to start graduate school and only shortly after that Nozomi announced to the lab that she was accepting a position at Cornell, and that the lab would be moving at the end of the year. So okay, we're going back to Cornell!

I feel like each main milestone in my scientific education and training has been shaped by the culture and the opportunities that were available to me at CHESS. I was able to come in as an undergrad with training in biology and chemistry and be trained by truly incredible scientists. To have the kind of culture and environment where I knew that I could go and ask questions of anyone and just say, “Okay, here's what I'm dealing with. What do you think?” It's just such a great environment for that. I think that my educational experiences have absolutely been shaped by the people there.

Q: How did your experience as a summer student lead to your decision to pursue a PhD at this same institution?

A: I think that the Cornell summer program really opened the door and allowed me to enter into this space where I was able to fall in love with synchrotron science and be supported in it. One of the things about being a community college transfer student that I realized, and from talking to some of my professors, is that usually transfer students are just slammed when they transfer into Cornell because it's very academically challenging and rigorous. They say to expect to take a one-point GPA plummet. And I found that to be true, but also the people around me, Richard, Sol and Jeney, were integral for me to be able to make that successful acclimation. I really lucked out that this opportunity brought me into a lab where I just absolutely fell in love with the work.

The summer program allowed me to enter into this field that I probably wouldn’t have even thought about otherwise. I would have been too intimidated by the physics. It was super interesting to me, but I wouldn’t have started out otherwise because I would have thought that it’s not possible for me to be successful here.

I think it was all about having that door opened for me and being welcomed into the scientific environment and be supported in being able to learn, and being able to step up to the challenge. I wouldn't have been able to pursue this path otherwise. It all started with the SERCCS program, opening the door, and letting me into this space and giving me the tools that I needed to be able to be successful.

Also, because of Richard Gillilan and the SERCCS program, I was introduced to Sol and because of him I was introduced to Nozomi. You know, I don't really think about it very often, but when I do, I'm just kind of blown away by how lucky I was and how formative that initial change in my trajectory was during that time while I was transferring from community college into Cornell. It changed my whole life. The thing that I like to think of is luck. I’ve heard of luck as being when preparation and opportunity coincide, and that I was really, really lucky at several points. And that luck is because CHESS is fostering this environment where students at any level can come in and partake in these projects.

I think it's really cool that I was able to spend the last nine years in synchrotron science. But not everybody loves it or is made for it. It can be intense, like when you have a beam time that lasts for 72 hours and during that time your life revolves around your experiment. You must drop everything else in your life, and the only thing that matters is making sure that it's successful and that can be hard. That's hard for people who don't have families, and I have a son who has been with me throughout this process. Luckily I've had a lot of people in my life who have supported us through. So not only is CHESS special, but Cornell is special too, because it's founded on this principle of any person, any study, and I have found that to be absolutely true and integral to so many of the experiences that I've had.

Q: Did the laboratory environment at CLASSE help foster collaboration and interdisciplinary work for you? Were there any examples of collaborative projects or initiatives that you were involved with as a summer student or as a Ph.D. student?

A: Absolutely, yes. I think the collaborative and interdisciplinary nature of the lab environment is integral to designing an experiment. It's almost impossible not to be interdisciplinary when we're providing X-ray experimental methods to biologists or to chemists. We have to be able to incorporate all of the different factors that concern their work. So, in order to perform an x-ray experiment on a biological system, you have to have information from each of those fields determining the way that you set it up.

Here's a specific example: the anoxic small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) experiment. We designed it so that it can accommodate biological samples that contain reactive metal centers which are often susceptible to oxidation, and that's why they need to be prepared and studies an anoxic environment. Metal centers often have characteristic absorbance profiles based on their oxidation state or reaction state. In designing this setup, we built in a full range UV spectrometer so that a researcher can collect the full range of UV-vis absorbance from 200 to 900 nanometers, and in doing that, you're able to characterize the absorbance properties of your sample. So, we intentionally incorporated this tool in-line so that we could characterize the metal centers of the samples. Alternatively, the standard aerobic SAXS experimental set up only allows for in-line absorption measurements at one wavelength (a280).

Another example is with the high-pressure SAXS setup. One of the things that I worked on between undergrad and beginning my Ph.D. work, was looking at the temperature range that we would be able to subject samples to while under high-pressure. As I was doing this, I was thinking about the temperature ranges in terms of what's physiologically relevant for these molecules. For example, if we're looking at a biological system that is active in deep sea vents, we’re thinking about the environment of these organisms and how we can replicate that as closely as possible in our experimental design.

That's really what I think of when I think of interdisciplinary, and the environment at CHESS is super supportive of those kinds of experiments. You have people who are experts in many different areas and you're coming in with a new perspective as a student. The culture at CHESS is supportive of that and you're never dissuaded from asking questions. The people there are great at meeting you where you're at. Richard Gillilan especially is exceptional at this. When he's working with students, Richard is able to distill the knowledge that's necessary to perform an experiment or to do a project, to the current level of the student. So, when I came in as a community college student with experience in biology and chemistry, and very little experience in physics, he was able to meet me there and bring me to the point where I could be an effective researcher in that highly physical environment.

Q: As a Ph.D. candidate, what were the most valuable lessons or skills that you acquired while you were at Cornell and in your program?

A: If I were to answer in one sentence, I think one of the main scientific skills that I gained from doing my Ph.D. in the Ando Lab, was to be able to think critically about every single feature of my experiment. Why am I doing it, what am I hoping to achieve? What are the indicators of success or efficacy? The whole lab is amazing at giving constructive critique, and it is very clear that the purpose of the critique is to improve your skills and to help you develop as a scientist. So I've gotten to the point where, as I was designing an experiment, I was thinking:

I'm going to have to explain this to people and I need to be able to justify what I'm doing. Having that critical perspective throughout the course of designing an experiment is crucial.

Q: How did CLASSE best support your professional development through your future journey? Were there any specific resources, workshops or opportunities that were particularly beneficial to you?

A: One unique thing that happened at CLASSE, and I think that speaks to the global scientific experience, occurred after my first year. The second summer that I was a researcher at CHESS, I was able to be connected to researchers at a synchrotron in France and do a project with them for a couple of weeks over the summer. That was really cool.

They also provide different seminars and workshops to bring people within the field up to speed on more advanced techniques like the high-pressure SAXS and crystallography, which is a rapidly expanding field right now. So, as a graduate student, I was able to be involved as one of the presenters teaching other researchers about our techniques. I was also involved for several years as a student as well towards the beginning; those were really fun to be a part of.

Q: What advice would you give to current or prospective community college students who aspire to pursue a career in scientific research, especially in accelerator-based science fields?

A: I think imposter syndrome is something that I experience deeply as a person coming in from community college background. Entering Cornell, and into these high-level research environments, can be very intimidating. A mentality that I developed as a coping mechanism, I think, is to just show up anyway. It's to just show up and do my best, to not let the fear stop me. Like even if I was experiencing fear about something specific, or fear of being inadequate, it's best to just show up anyway, and to just give it your all. And that's what I would say to myself: okay, let's say I am a complete fraud, I'm totally undeserving of this and they’re going to see right through me, so what. I'm going to show up and give it my best anyway. Then, if it all falls apart, I can at least walk away knowing I gave it my all, I'm not going to regret not doing more, you know? I think the process of slowly disproving that imposter syndrome it's difficult. I mean, I'm sure I'm still going to feel it as I'm starting a postdoc in a different field in a physics department (you know, with no formal training in physics). But I'm just going to show up and do my best, and hopefully I will be able to contribute something of worth. I think the most important thing is to not let the fear hold you back, show up and do your best, and let the pieces fall where they may.